This introduction describes a set of questions that form the basis of a systems approach to health and care design and continuous improvement.

Contents

Introduction

Questions are an important part of any toolkit, but are only as good as the people that use them and only effective when used to accomplish appropriate activities. Questions are useful to novices and require little instruction to benefit the improvement process. Questions in the hands of experts may feel like an extension of the master working their trade, used for their intended purpose or adapted for other purposes. The questions here have been designed to provide focus on people, systems, design, risk and management perspectives.

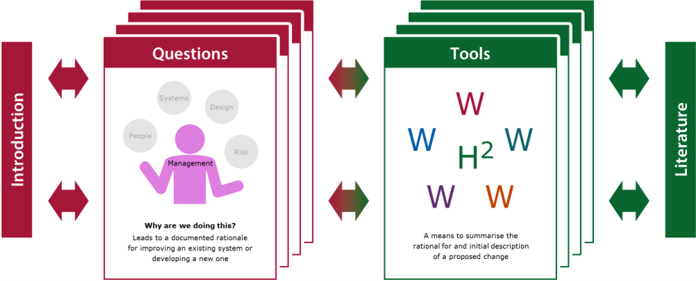

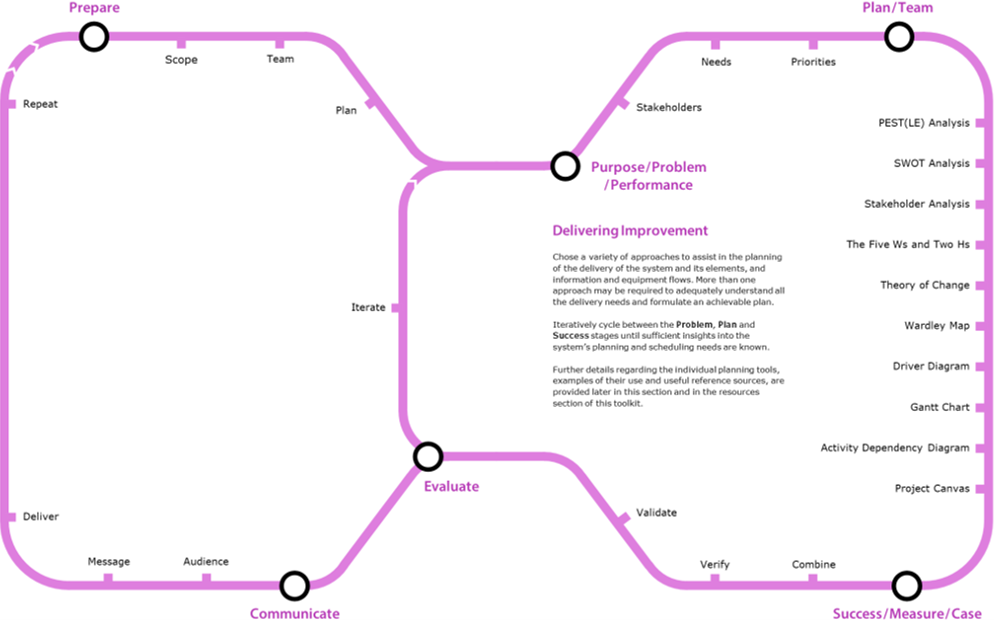

The questions in this toolkit are derived from the Engineering Better Care report. Simple guidance is provided for their use and reference given to resources that describe them in more detail. The intention is not to provide full instructions for their use here, rather to point to their existence and indicate where they might be used and which tools might support them. They are catalogued according to their most likely contribution to the key perspectives of the systems approach, but may be used more broadly.

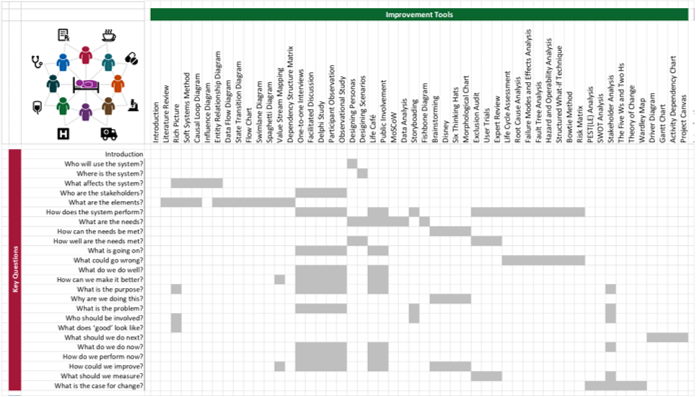

Tools may be mapped to questions to assist in their selection. More than one tool may be used for any particular purpose and this is often encouraged. The mapping provides clear indication as to how tools might be used to support the answering of the questions, but is not expected to exhaustively show where activities have actually been used in practice.

As already seen in the Improving Improvement section of this toolkit, The Engineering Better Care report describes the development of a systems approach to health and care design and continuous improvement, taking inspiration from both the healthcare and engineering sectors. It takes a broad view of systems (or systems of systems) as a set of elements that include people, processes, information, organisations and services, as well as software, hardware and other systems that, when combined, have qualities that are not present in any of the elements themselves. It then proposes that a systems approach is a process that integrates four key and complementary perspectives:

- People: understanding of interactions among people, at the personal, group and organisational levels, and other elements of a system in order to improve overall system performance

- Systems: addressing complex and uncertain real world problems, involving highly interconnected technical and social elements that typically produce emergent properties and behaviour

- Design: focusing on improvement by identifying the right problem to solve, creating a range of possible solutions and refining the best of these to deliver appropriate outcomes

- Risk: managing risk, based on the timely identification of threats and opportunities in the system, assessment of their associated risks and management of necessary change.

Each of the four perspectives of people, systems, design and risk can be seen as individual components within an overall improvement process. However, while each uniquely contributes to a systems approach, they are inextricably linked and the challenge is to integrate them within a useful, versatile and systematic process that repeatedly delivers results. The Engineering Better Care report presents the improvement process as an ordered set of questions, based on the individual perspectives, that should be asked until the current system is improved to delivered something measurably better into service. That sequence of questions has been extended to introduce questions related to the management of the improvement process.

The following sections describe the questions relating to the people, systems, design, risk and management perspectives associated with an improvement process. In each case, a brief introduction to the perspective is provided, along with details of the questions related to that perspective and tools that may be used to help answer those questions. An introduction to the literature related to each perspective is also provided.

Text list of Questions

Management

People

Systems

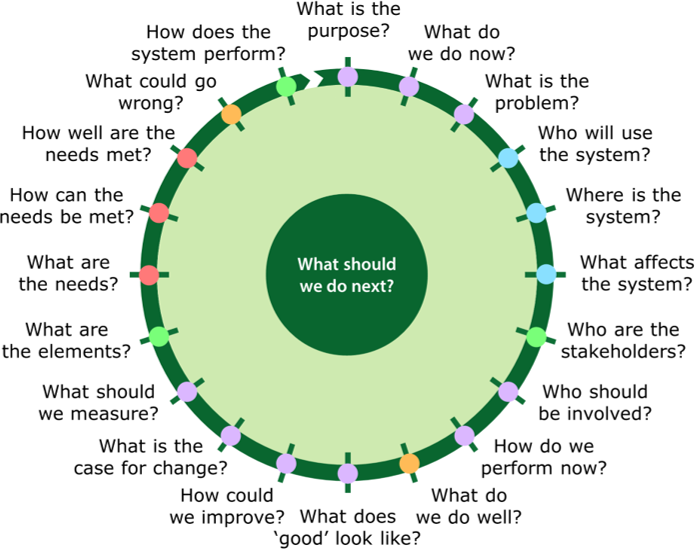

Pictorial list of Questions

You can click on any of the images below to find out more about that question.

Cards for each of the questions are available in the boxed version of this toolkit. If you would like further information on how to get hold of these cards, please contact edc-toolkit@eng.cam.ac.uk

Management

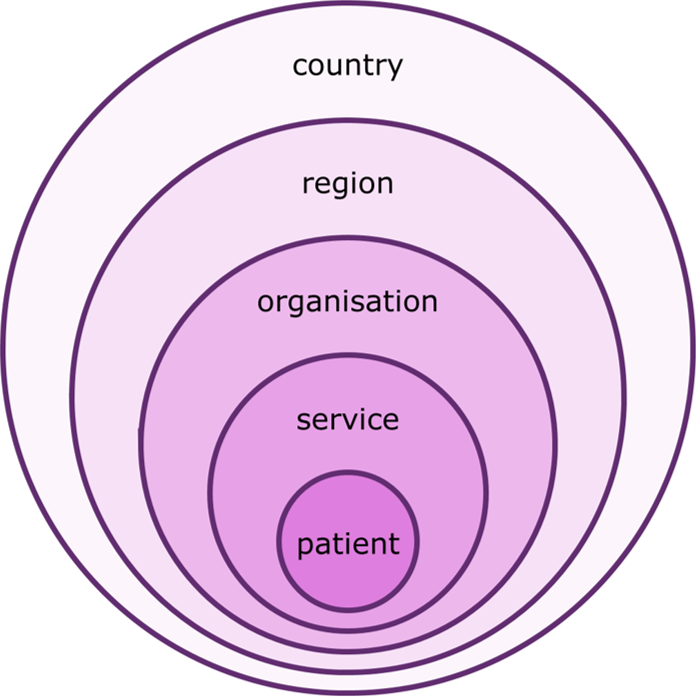

The successful management of improvement in complex systems is a practical challenge requiring an understanding of people, systems, design and risk perspectives along with improvement management skills. In this context, the questions associated with these perspectives have been rationalised where they overlap and improvement programme questions have been added. The have then been reordered to provide a natural sequence for all the questions. The resulting Systems Approach can be applied to the design and improvement of systems at all extremes of scale, with service level improvement taking place at a local level or within a wider context that may subsequently require changes at the organisation level and cross-organisational level.

Why are we doing this?

The question ‘Why are we doing this?’ leads to a documented rationale for improving an existing system or developing a new one, with regard to the timing, source and particular nature of the trigger. It is likely to include a variety of activities that can help capture this rationale, for example:

- Record the trigger for the improvement process

- Identify the initial scope of the improvement process

- Ensure that an appropriate team is assembled

All improvement processes are initiated, and potentially shaped, by their trigger1, which may classed as:

- Strategic — where risk reduction and improvement is part of an ongoing strategic initiative.

- Incident — where an event has resulted in actual or potential harm to patients or clinicians.

- Local — where the potential for incidents has been identified locally.

- Routine — where a team or individual wishes to check the integrity of their service.

- Improvement — where changes are planned to an existing service or system.

- New — where a new service is to be introduced into practice or an existing one decommissioned.

- Technology — where new equipment or technology is to be introduced to an existing service.

- Estates — where estates or buildings are being built, refurbished or maintained.

- Staff — where new staff are to be introduced to an existing service or exiting staff levels are changed.

- External — where specific strategic changes or checks are externally requested.

- National — where teams are encouraged to propose and deliver national service improvements.

A clear understanding of the trigger helps to identify the initial scope of the improvement and ensures that an appropriate team is assembled to initiate any subsequent improvement process. Whether the trigger relates to people, systems, design or risk, a systems approach should consider all of these perspectives in a seamless and integrated way.

Footnotes

- Engineering Better Care, a systems approach to health and care design and continuous improvement. Royal Academy of Engineering, London, UK, 2017.

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

What is the purpose?

The question ‘What is the purpose?’ leads to detailed description of the purpose of the current system within its wider context, based on an understanding of the system and the behaviour and level of performance it is expected to deliver. It is likely to include a variety of activities that can help develop this description, for example:

- Provide a detailed description of the purpose of the system

- Understand the wider context of care and therefore of the system

- Identify factors that influence the performance of the system

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

What do we do now?

The question ‘What do we do now?’ leads to a detailed description of the current system architecture and its observable behaviour based on observation, active enquiry and analysis of available information. It is likely to include a variety of activities that can help develop this description, for example:

- Provide a detailed description of the current system

- Understand the operation and behaviour of key pathways

- Identify stakeholders and users and their current needs

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

How do we perform now?

The question ‘How do we perform now?’ leads to the qualitative and quantitative evaluation of the performance of the current system, with particular regard to the key elements of the system and their expected behaviour. It is likely to include a variety of activities that can help build this understanding, for example:

- Analyse available quantitative data relating to the current system

- Gather qualitative information relating to the current system

- Identify strengths and weaknesses of the current performance

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

What is the problem?

The question ‘What is the problem?’ leads to a clearly articulated view of a better system based on an understanding of the current system and the level of improvement desired to achieve acceptable system performance. It is likely to include a variety of activities that can help build this view, for example:

- Describe the current system and its performance

- Describe a future system and its potential performance

- Define the challenge based on the desired improvement

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

How could we improve?

The question ‘How could we improve?’ leads to a preliminary description of a better system architecture and its intended behaviour, with regard to the current system architecture and its behaviour. It is likely to include a variety of activities that can help develop this description, for example:

- Provide a preliminary description of a future improved system

- Describe the operation and behaviour of key pathways

- Identify stakeholders and users and their future needs

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

What does ‘good’ look like?

The question ‘What does ‘good’ look like?’ leads to a common and clearly articulated understanding of success and how it might be recognised, with particular regard to reasonable constraints on its delivery. It is likely to include a variety of activities that can help build this understanding, for example:

- Dream of an ideal goal where there are no constraints

- Define a feasible goal reflecting reasonable constraints

- Create a balanced and viable case for change

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

What should we measure?

The question ‘What should we measure?’ leads to the identification of possible performance indicators for the improved system, with regard to the proposed system architecture and its intended behaviour. It is likely to include a variety of activities that can help with this identification, for example:

- Describe the intended performance of the improved system

- Identify possible performance indicators for the improved system

- Outline approaches to measure the agreed performance indicators

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

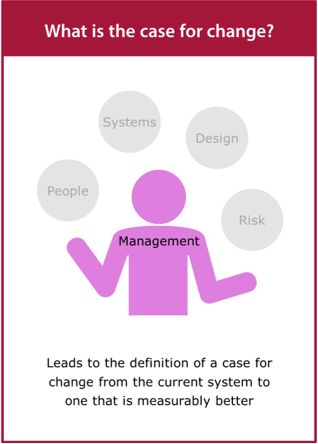

What is the case for change?

The question ‘What is the case for change?’ leads to the definition of a case for change from the current system to one that is measurably better, with regard to the proposed system architecture and its intended behaviour. It is likely to include a variety of activities that can help with the development of the case for change, for example:

- Compare the current performance to that which is measurably better

- Estimate the value of the proposed system improvement

- Offset the likely value of the change against the cost of change

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

Who should be involved?

The question ‘Who should be involved?’ leads to a common and clearly articulated understanding of who should deliver the improved system, with regard to the differing needs at different stages of the delivery. It is likely to include a variety of activities that can help build this understanding, for example:

- Choose a team that reflects the key stakeholders

- Include members who are active in the current system

- Include members who are able to facilitate change

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

What should we do next?

The question ‘What should we do next?’ leads to the ongoing development and execution of a plan of action to deliver the system in a timely manner, with regard to the resources available for its delivery. It is likely to include a variety of activities that can help with this development, for example:

- Identify the next steps critical to achieving progress

- Build in iteration and contingency to allow for potential problems

- View the plan as a starting point rather than a fixed schedule

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

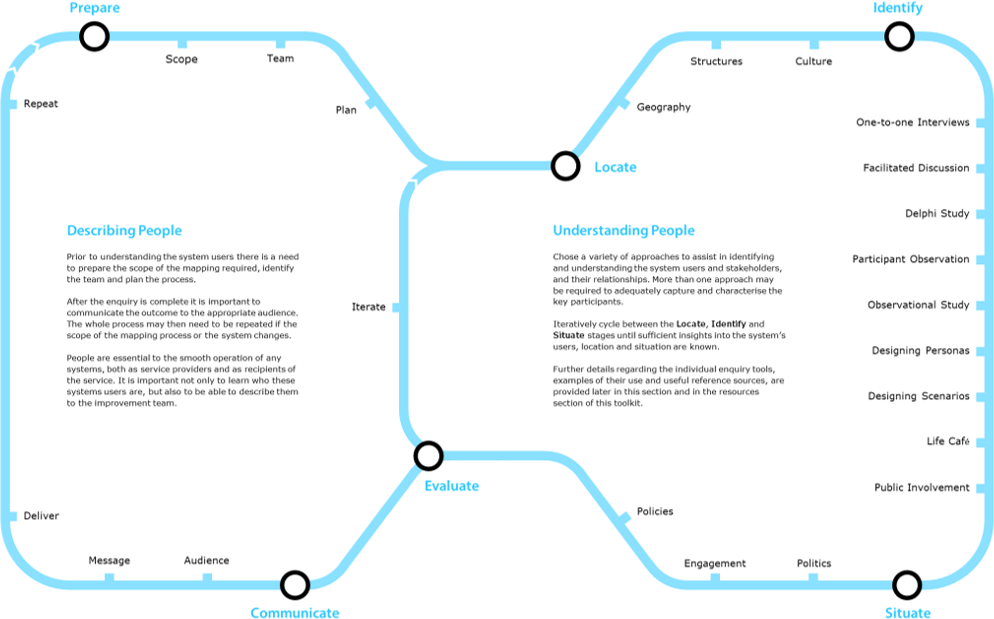

People

The contribution of treatments, equipment, systems, processes and protocols are undeniably critical to health and care provision; however, it is people who ultimately affect the quality of that delivery. An appropriate awareness of people applies not only to the recipients of care, but also to the providers of care. It is important to acknowledge the diversity of the population and that health and care services should be accessible to, and usable by, as many people as reasonably possible, regardless of age or health condition. Equally, a chief executive can have a significant impact on an organisation, through their actions and behaviour, creating a culture that values the importance of the quality of relationships between employees and, most critically, the people in their care.

People are diverse in their size and capability, whether they are members of the public, patients or providers of care. Systems should be designed to be accessible to, and usable by, as many people as reasonably possible.

The success and effectiveness of a system are dependent on consideration of the people within the system, its context or place and the policy defining its operation. This can be represented as a series of iterative identify, locate and situate cycles where it is crucial to pay attention to provider/patient relationships as well as the relationships between health professionals, and how these can be enhanced by providing appropriate technologies, systems and policies to deliver a quality of care judged by the degree of warmth and reassurance shown to both colleagues and the people receiving care.

People are at the heart of an effective systems approach1, permeate all stages of the development and delivery of a system, and are rightfully central to the systems, design and risk perspectives.

A people perspective serves to involve patients, practitioners and the public to ensure that the systems created are truly fit for their intended purpose and reflect a deep understanding of how knowledge, competence and culture enables people, individually and corporately, to deliver and receive health and care within a complex socio-technical environment2.

Footnotes

- New care models: empowering patients and communities, a call to action for a directory of support. NHS England, Redditch, UK, 2005.

- Implementing human factors in healthcare, ‘taking further steps’. Clinical Human Factors Group, 2013.

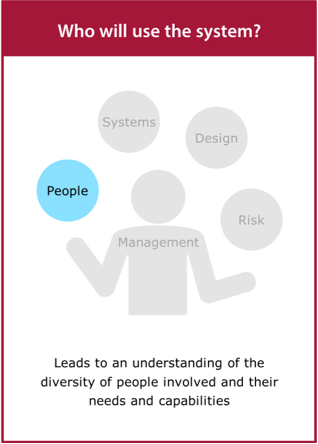

Who will use the system?

The question ‘Who will use the system?’ leads to an understanding of the diversity of people involved and their needs, capabilities and behaviours, including reference to the means by which they will engage with the design of the system. It is likely to include a variety of activities to develop this understanding, for example:

- Identify all the people who will use the system

- Co-create the system with system users and change facilitators

- Ensure accessibility for all systems users

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

Where is the system?

The question ‘Where is the system?’ leads to an understanding of the physical, organisational and cultural context of the system, including reference to organisation and culture, as well as the demographics and needs of the local population. It is likely to include a variety of activities to develop this understanding, for example:

- Capture the needs of the local population

- Identify related or adjacent systems of care

- Understand the current culture relating to the delivery of care

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

What affects the system?

The question ‘What affects the system?’ leads to an understanding of the political and policy landscape within which the system is situated, including reference to policy opportunities and constraints, and the political landscape. It is likely to include a variety of activities to develop this understanding, for example:

- Understand the local and national political landscape

- Encourage a systems approach to the provision of care

- Identify health and care policies that put patients first

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

Systems

A system is a set of elements: people, processes, information, organisations and services, as well as software, hardware and other systems that, when combined, have qualities that are not present in any of the elements themselves. A systems perspective takes a holistic approach to understanding this complexity that enables the delivery of intended outcomes based on the way in which a system’s constituent parts relate to each other and to the wider system.

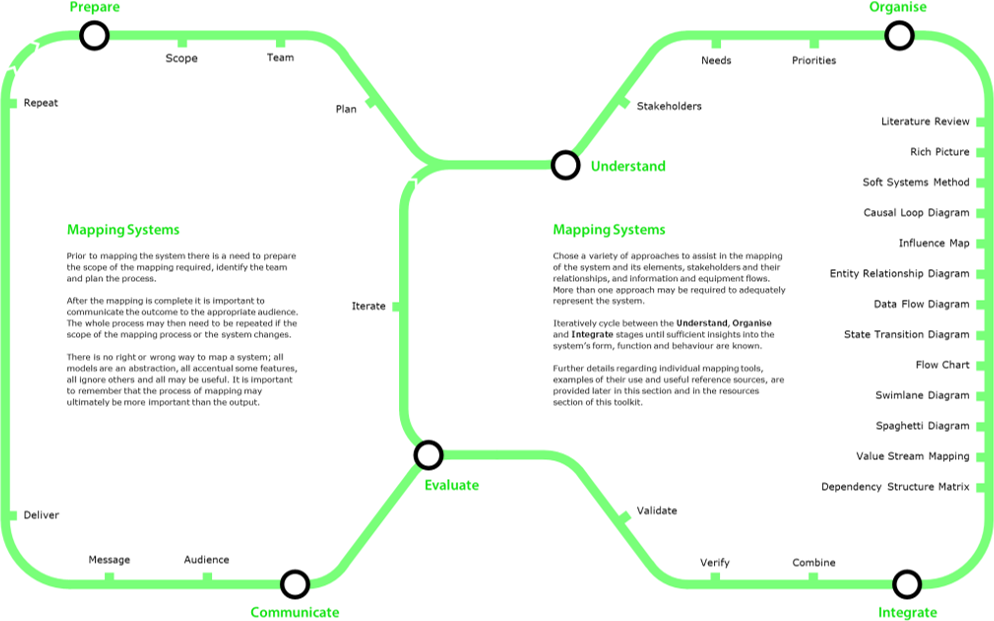

The design of a system can be considered to be made up of a series of iterative understand, organise and integrate cycles that enable a team to progress from identifying the stakeholders and their needs through to organising a system of elements and interfaces that are subsequently designed, integrated, validated and delivered to satisfy those needs.

Some systems are simple, others are chaotic1. Some are complicated with many elements, but operate in patterned ways, others are complex with features whose interactions are continually changing. It is the co-production of health outcomes with the patient, often across a number of systems rather than with any individual health and care system, that can add significant complexity and uncertainty, leading to behaviours not expected when focus is limited to individual systems. As a result, the solution to a challenge may actually involve changing another system and not the one where the problem or symptom is appearing, relying on collaboration and an integrated holistic view of the systems2.

Footnotes

- The new dynamics of strategy sense-making in a complex world. Kurtz and Snowden, IBM Systems Journal, 42(3):462-483, 2003.

- Creating systems that work: Principles of engineering systems for the 21st century. Royal Academy of Engineering, London, UK, 2007.

Who are the stakeholders?

The question ‘Who are the stakeholders?’ leads to a common and accepted understanding of the range of stakeholders and their individual interests, needs, values and perspectives. It is likely to include a variety of activities that can help build this understanding, for example:

- Identify system stakeholders and capture their needs

- Analyse the stakeholder needs and define priorities

- Draft the business case(s) for system change

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

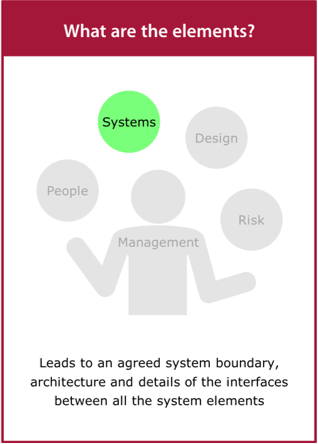

What are the elements?

The question ‘What are the elements?’ leads to an agreed system boundary and architecture comprising a description of existing systems, requirements for new systems and details of the interfaces between them. It is likely to include a variety of activities that can help deliver this architecture, for example:

- Agree functional and information requirements

- Define the system architecture, boundary and interfaces

- Agree the system integration and evaluation plan

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

How does the system perform?

The question ‘How does the system perform?’ leads to a complete, operational system that is proven to meet the stakeholder requirements and is fit for its intended purpose. It is likely to include a variety of activities that can help deliver an integrated system, for example:

- Combine the system elements to build the complete system

- Verify and validate the system performance

- Monitor the system performance when it is in use

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

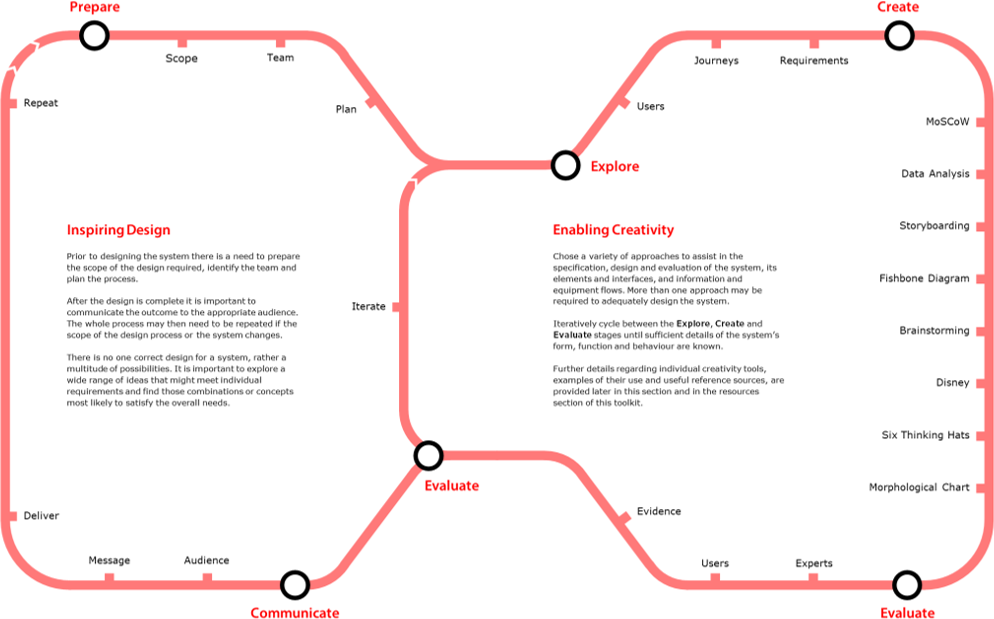

Design

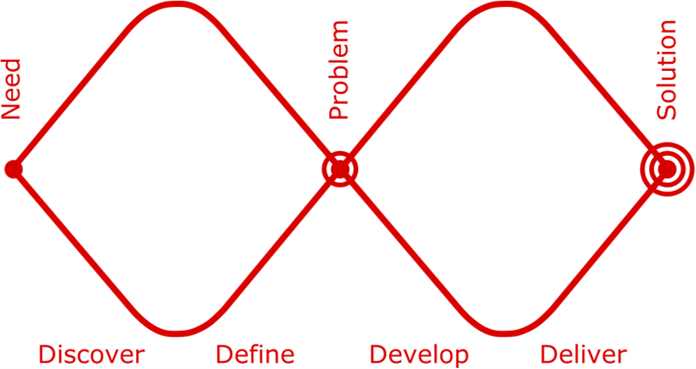

It has been argued that many problems addressed by designers are wicked problems, defined as a class of problems that are ill-formulated, where the information is contradictory, where there are many stakeholders with conflicting values, and where the behaviours in the system are confusing. In response, the Design Council’s double diamond1 comprises an initial analytical phase, which determines all of the elements of the problem and specifies the requirements for a successful solution, and a synthesis phase, which generates a range of possible conceptual solutions and an implementation plan.

In practice, design is iterative in nature, comprising multiple explore, create and evaluate cycles that enable a team to progress from understanding the need through to developing the solution. Design can be seen as a risk reduction exercise, set to maximise the chances of delivering the right solution to the right problem reflecting the right need.

The design process is typical of those used to address wicked problems2, where it is not only highly creative, but also very likely to be highly iterative in order to deal with the intrinsic uncertainty in understanding the real needs and finding an appropriate solution. This is evidenced by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s iterative model for improvement (Aim, Feedback, Changes, Plan, Do, Study, Act) often encountered in health and care, where the planning stage is particularly influential in ensuring the delivery of safe systems into practice.

Footnotes

- Eleven lessons managing design in eleven global companies. Design Council, London, UK, 2007.

- Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Rittel and Webber. Policy Sciences, 4(2):155-169, 1973.

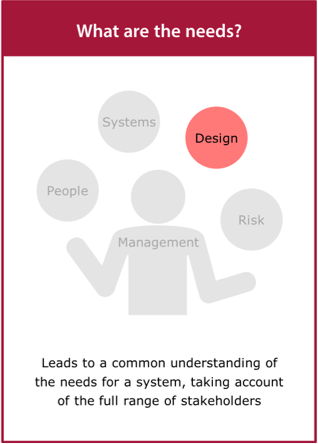

What are the needs?

The question ‘What are the needs?’ leads to a common and accepted understanding of the likely needs for a system, taking account of the full range of stakeholders. It is likely to include a variety of activities that can help build this understanding and draw the findings together, for example:

- Observe users to reveal what they really need

- Generate personas to represent key users

- Describe typical user journeys within the system

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

How can the needs be met?

The question ‘How can the needs be met?’ leads to a range of possible concepts and corresponding system solutions that would help meet the needs and criteria for success identified by the explore phase. It is likely to include many of the activities commonly thought of as conceptual design, for example:

- Generate a wide range of solution ideas that could satisfy the needs

- Make prototypes to demonstrate the solutions’ potential

- Select the best solution(s) for development

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

How well are the needs met?

The question ‘How well are the needs met?’ leads to an evaluation, both virtually and in practice, of possible system concepts that could meet the needs and criteria for success identified by the explore phase. It is likely to include activities to provide evidence that the needs are actually met, for example:

- Test the system with experts and users

- Evaluate how well the stakeholders needs are met

- Present evidence from the system evaluation

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

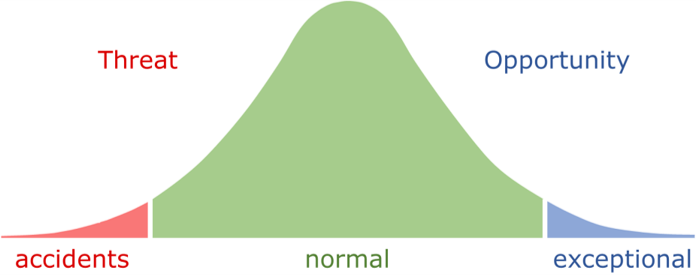

Risk

Engineering risk and safety management methods, such as Failure Modes and Effects Analysis, Hazards and Operability Analysis and Fault Tree Analysis, are used to identify potential threats and opportunities within a system and to manage their likelihood and/or impact on people, property, progress or profit. The role of risk management is to identify, assess and control the level of known risk, accepting the inherent threat or opportunity that may be present within the system, in particular with complex medical interventions and in the distributed system of social care.

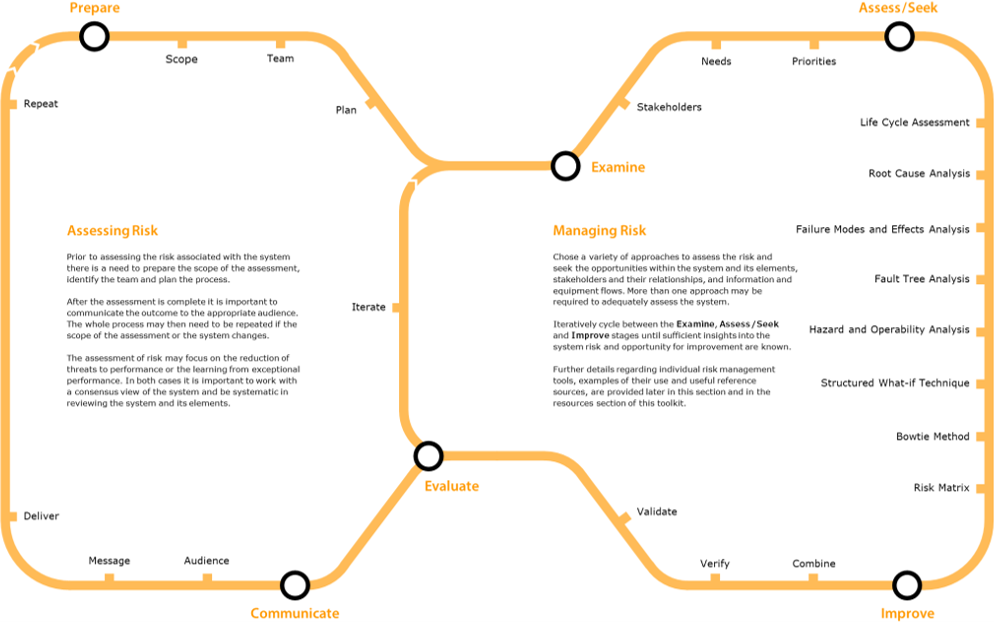

It is useful to consider the process of risk management to be made up of a series of iterative examine, assess / seek and improve cycles that enable a team to progress from understanding what is known about the system through to developing interventions to manage the risk presented by the system. Active risk management is appropriate at all stages of a product or service lifecycle, from early conception, through use to disposal.

Risk can be referenced to a system’s ability to deliver high-quality, cost-effective care, where quality is defined as the combination of clinical and cost effectiveness, patient safety and patient experience1. Risk management is commonly used as a clinical tool for the prospective analysis of an individual patient’s risk, with or without a particular intervention. However, it may also be used to evaluate the risk in sustaining or not achieving the desired outcomes for a population of patients, the efficiency of a care process or the finances of a care provider2. Different stakeholders may have different risk priorities within the same system and risk tolerance levels will vary with time and be dependent upon the context of each specific care delivery system or process. Risk may also be attributed to uncertainty in performance where mitigation will likely focus on the identification of the sources of such variation and their reduction.

The identification and exploitation of opportunities to learn from exceptional performance represents the alternative face of risk management. This view has gained much traction in recent years as a complementary activity alongside traditional methods of risk management1. In practice, both approaches should be used to be able to take an holistic approach to proactive risk management.

Footnotes

- From Safety-I to Safety-II: A White Paper. Hollnagel, Wears and Braithwaite, The Resilient Health Care Net, 2015.

- Design for patient safety: a system-wide, design-led approach to tackling patient safety in the NHS. Department of Health and Design Council, London, UK, 2003.

What is going on?

The question ‘What is going on?’ leads to an understanding of the system architecture and details of the interfaces between the elements, which takes account of the range of stakeholders and their needs. It is likely to include a variety of activities that can help build this understanding, for example:

- Outline the goals of the risk assessment

- Describe the system and identify critical risk stakeholders

- Agree acceptable levels of system risk

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

What could go wrong?

The question ‘What could go wrong?’ leads to a systematic assessment of the likelihood and potential impact of threats within a system, which takes account of the nature, frequency and source of the threats. It is likely to include a variety of activities that enable this assessment, for example:

- Identify threats to the sustained performance of the system

- Evaluate risks associated with the threats and their detectability

- Specify mitigation needs to reduce unacceptable risks

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

What do we do well?

The question ‘What do we do well? leads to a systematic assessment of the likelihood and potential impact of opportunities within a system, which takes account of the nature and source of the opportunities. It is likely to include a variety of activities that enable this assessment, for example:

- Identify opportunities to enhance the performance of the system

- Evaluate benefits linked to the opportunities and their achievability

- Specify improvement needs to exploit the opportunities

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

How can we make it better?

The question ‘How can we make it better?’ and leads to range of possible solutions that would help mitigate the threats or exploit the opportunities, which takes account of the stakeholders’ appetite of such risk. It is likely to include a variety of activities that enable this implementation, for example:

- Propose actions to manage the risk within the system

- Implement potential actions within the system

- Review the assessment in a timely manner

Back to text list of Questions | Back to pictorial list of Questions

Feedback

We would welcome your feedback on this page:

Privacy policy. If your feedback comments warrant follow-up communication, we will send you an email using the details you have provided. Feedback comments are anonymized and then stored on our file server

Read more about how we use your personal data. Any e-mails that are sent or received are stored on our mail server for up to 24 months.