These case studies explore the use of a systems approach in the development, delivery or improvement of a range of engineering and healthcare systems.

Contents

Engineering

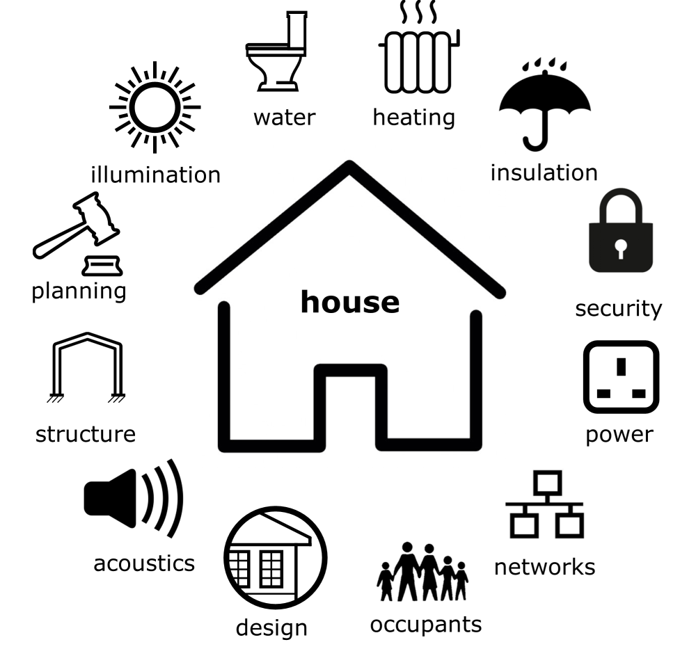

The Home

Consider a house that is made up of a number of systems that co-exist to ensure that a house becomes a home. Some are discrete yet interconnected (water, heating, power, security and networks) while others are naturally more holistic (design, structure, planning, illumination and insulation).

The delivery of any particular system requires expert knowledge of that system and how it will interface to the whole. The heating specialist cannot develop an appropriate solution without knowledge of the design, structure and insulation, nor can they deliver the solution without detail of the power and water systems. Each specialist will have a different perspective on the house, yet architects, and subsequently builders, act as system integrators, delivering homes with emergent properties greater than the sum of the individual parts. For example, the energy rating of a house depends on a combination of design, structure, insulation and heating, while its desirability may depend on these and many more factors.

A good house design is critically dependent not only on its architectural properties but also on engineers systematically evaluating its performance. Structural engineers model the resilience of the house under all expected loads, insulation specialists model its thermal properties and heating engineers size their systems based on these results and the likely behaviour of its occupants. Utility providers model the water, waste and power requirements, particularly where multiple houses are being built. Local authorities model the impact of new homes on the environment and on local services such as schools, hospitals, highways and waste collection. Governments model the demand for new homes based on expected patterns of migration. As a result, the house may be seen as an element in an extended system of systems.

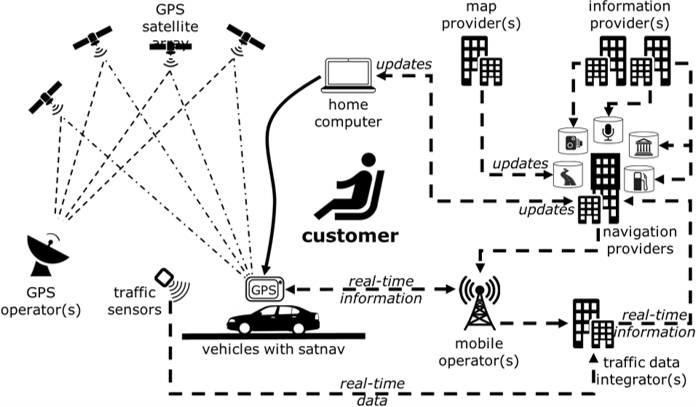

Satellite Navigation

Engineered systems often rely for their operation on a number of independent, but interrelated systems. For example, a satellite navigation system depends on the action and operation of a number of service providers. The degradation of any one of these systems or the interfaces between them will have an adverse impact on the navigation experience and possibly the safety of the vehicle occupants.

Further systems, such as rocket launch vehicles, mapping technologies and voice recording studios, are also required to enable the successful deployment of a navigation system. Inevitably, the focus of individual development teams for these systems would have been different, particularly since GPS satellite arrays and mobile telecommunication systems were not initially designed with commercial navigation systems in mind. However, the architects of satnav systems would have had a holistic vision for their system of systems and robust descriptions of the interfaces relevant to the individual elements and to the whole.

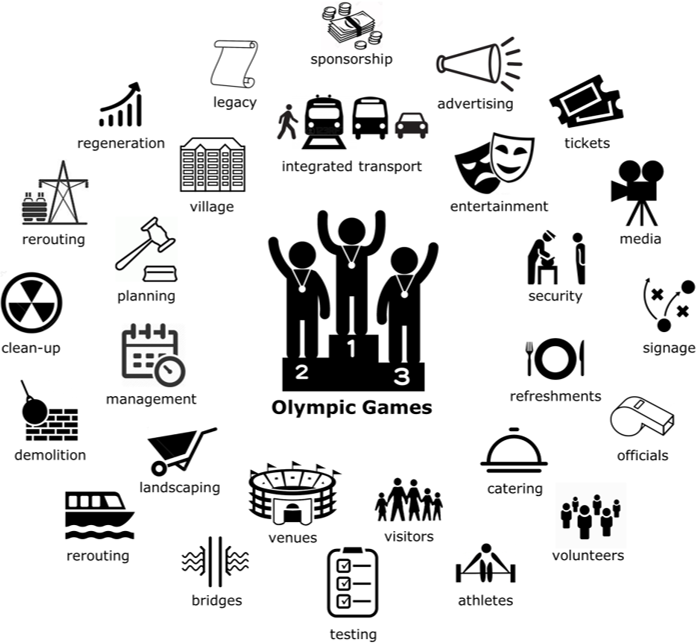

The Olympics

Systems are designed at many levels of scale from the micro to the macro, where they often involve complex interactions between people, physical infrastructure and technology. This is exemplified by the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games: 205 competing nations, 17,000 athletes and officials, 26 different sports, covered by 22,000 journalists and over 10 million tickets to be sold. An Act of Parliament established the Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA) with a budget of £8 billion to deliver the infrastructure, venues, athletes’ village and transport in a sustainable manner and to leave a lasting legacy1.

The ODA commissioned a delivery partner to manage the construction of the Olympic Park in East London and to manage the complex logistics on the site. Both were similarly incentivised to ensure an alignment of objectives between the two teams to deliver a programme over six stages: Plan, Demolish, Build, Test, Games and Legacy. Their common purpose was to deliver the best Games ever and a lasting legacy for London. A number of interrelated elements were developed relating not only to the physical infrastructure required, but also to the practical organisation of the Games.

Footnotes

- Engineering the Olympics: The 2011 Lloyd’s Register Educational Trust Lecture. Royal Academy of Engineering, London, UK, 2001

The Olympics

The success of the Games and its legacy was critically dependent on early decisions relating to the Olympic Park, a challenging site that needed significant redevelopment. Both the immediate and future needs were realised through the provision of temporary or reconfigurable sports venues, removable bridges alongside permanent structures and landscaping for the longer term. Innovative engineering delivered world-class, cost-effective buildings. Modelling and simulation of people flows informed provision of signage, refreshments, security, helpers, transport and information for visitors. Testing of new venues identified problems early, leading to better provision for athletes, officials and visitors. Extensive planning and risk management by the engineering-led team made the complex merely complicated. A systems approach, combined with tried and tested engineering methods and tools, delivered real success on a massive scale.

Healthcare

A selection of examples from healthcare have been chosen and presented here to demonstrate that a systems approach is adaptable to all levels of scale, from service level through organisation to cross-organisation, and sufficiently versatile to apply across all areas of health and care. The case studies are representative of systems that are simple, complicated and complex and found at service, organisation and cross-organisation levels.

The following case studies of change or transformation projects aim to put the guiding questions and perspectives described in this toolkit into context. Whilst not all the projects described will have explicitly used a systems approach, the case studies highlight how they have taken into account the people, systems, design and risk perspectives in their work. Further case studies can also be found in the Engineering Better Care report.

Methotrexate

When a patient died as a direct result of failures in their own care an inquiry highlighted the need to review the use of oral methotrexate for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis1

Insights:

- Patients’ needs were at the heart of the system-wide review

- Changes required the cooperation of a variety of stakeholders

- Safety still relies in part on the actions of the patient

This case study is described in more detail later in this section.

1Methotrexate Toxicity. An Inquiry into the Death of a Cambridgeshire Patient in April 2000. Cambridgeshire Health Authority, 2000.

Esther

Esther inspired her local medical department to initiate a series of interviews and workshops to identify redundancies and gaps in medical and community care systems1

Insights:

- Esther represents elderly persons who have complex care needs

- Changes required the cooperation of a variety of stakeholders

- Deliver multi-provider care as if it were from the same provider

This case study is described in more detail later in this section.

1Sweden’s Esther Model: Improving Care for Elderly Patients with Complex Needs. Gray, Winblad and Sarnak, The Commonwealth Fund, 2016.

Community Care

Understanding people’s ability to respond to the challenges in accessing community care can lead to improvements that directly influence clinical outcomes

Insights:

- All health and care services make demands on their patients

- Patients need sufficient capabilities to meet service demands

- Making services more accessible improves patient outcomes

Day Surgery

Perioperative care during day surgery is known to influence patient outcomes and understanding those factors that most effect the patient is of critical importance

Insights:

- Patient outcome data can inform the care of individual patients

- Delphi studies can lead to a consensus view of patients risks

- Data analysis can lead to a better understanding of clinical actions

Global Health

In low and middle income countries where healthcare resources are limited, improvements in care are likely to rely on systems changes as well as new technologies

Insights:

- Mapping the system is crucial in identifying areas for improvement

- A systems approach needs to be carefully translated for local use

- Lessons learned have to be used sensitively to transform practice

Palliative Care

New approaches to palliative care are required in response to people’s changing needs and expectations within an increasingly resource constrained health service

Insights:

- Palliative care is often distributed across multiple care providers

- Palliative thinking is not just for palliative specialists

- Current approaches to care are not universally accessible

Emergency Care

Observing patterns of treatment in an emergency department led to the development of tools to identify and evaluate more robust patient flow management paradigms

Insights:

- Patient flow within the emergency department is complicated

- The physician in charge uses heuristics to manage flow

- Heuristics provide a classification of problem solving approaches

Public Health

Obesity among children is a significant challenge, requiring families, schools, food, community and healthcare services to work together resolve the crisis

Insights:

- A recognition of systems is key to sustainable success

- The value of building capacity and encouraging engagement

- The need to introduce coordinated strategies across the whole system

Inpatient Care

Central Venous Catheterisation has been associated with cases of retained guidewires in patients after surgery, as a direct result of a complex interaction between equipment and people

Insights:

- Retained guidewires is an observable ‘never event’

- Practitioners of all levels of experience can make errors

- Interruption at a specific critical time can lead to an error

Patient Flow

Patient flow through a hospital is dependent on the rate of arrival and the rate of departure, where the latter depends on the timely provision of care in a resource-limited environment

Insights:

- Patient flow out of a hospital is a complex systems challenge

- Misalignment of resources and goals create flow bottlenecks

- There is often a lack of senior leadership for the whole journey

Methotrexate

Local and national stakeholders, led by the National Patient Safety Agency, were engaged in making the design of methotrexate tablets, their prescription, delivery and monitoring safer for patients using it for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

Scope

Trigger

In 2000, a Cambridgeshire patient died as a direct result of failures in their care and treatment. The inquiry into their death highlighted the need to review the use of oral methotrexate for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in the UK. In this particular case, the patient had been taking a weekly dose of methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. The strength of methotrexate had been altered in error by her GP to a daily dose of 10 mg from the previous weekly dose of 17.5 mg. This was dispensed by a community pharmacy. The patient inadvertently overdosed on methotrexate and their immune system became severely compromised. The patient was later admitted to hospital with symptoms of a severe sore throat, where they continued to receive treatment at this high daily dose until the mistake was identified on the fourth day following admission.

Agree Aim Statement

Of the 13,000 medicines licensed for use in the UK at that time, oral methotrexate was one of only six that should have been taken weekly. Previously, 25 deaths and 26 cases of serious harm had been attributed to the incorrect use of methotrexate. More than half of the 167 adverse events associated with patients taking methotrexate between 1993 and 2002 were the result of the drug being prescribed on a daily basis. Some cases were due to errors occurring during the transfer of information from hospitals to GPs, others were due to problems with information technology systems that failed to give clear information on the frequency of dosing. The aim is to reduce to zero the number of deaths attributed to the misuse of oral methotrexate.

Context

Generate Scenarios

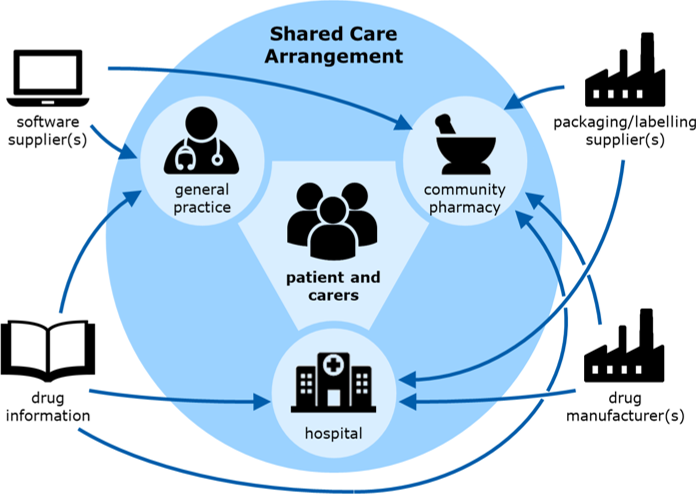

The system is in the UK and spans from the home to general practice to the community pharmacy to the hospital, working under a shared care arrangement.

Understand Patient Diversity

People who are actively using the system are those within the Shared Care Arrangement, such as patients with rheumatoid arthritis, their carers, GPs, pharmacists, phlebotomists and hospital doctors.

Understand System Context

There are three suppliers of methotrexate for the UK market. They provide 2.5 mg and 10 mg tablets that are similar in colour and size in 100 tablet bottles and 2.5 mg tablets in blister packs of 28 tablets.

Create System Maps

The management of patients taking methotrexate is organised using a Shared Care Arrangement, sharing responsibility for safe care between the general practice, the community pharmacy and the hospital. This forms the core of the system. In addition, computer software enabling the prescribing and dispensing of methotrexate is used, drug information leaflets and record books are provided, and the drug and packaging are required (see below).

Context

Create Stakeholder Needs

Stakeholders are those that have an interest in the successful performance of the system and can be described by their role title, need(s) and purpose:

- As a patient I need sufficient methotrexate so that I have relief from the pain resulting from my rheumatoid arthritis, I need methotrexate in an easy-to-open pack so that I am able to open the pack and easily retrieve the correct dose and I need to be confident that I am taking the correct dose of methotrexate so that I do not suffer adverse effects from the drug.

- As a general practitioner I need to ensure that the patient knows how to administer methotrexate so that there is no chance of the patient taking the wrong dose. I need to be sure that I prescribe the correct dose of methotrexate so that there is no chance of the patient taking the wrong dose, and I need to ensure that the patient’s bloods are monitored so that the dose can be controlled.

- As a hospital doctor I need to understand the particular challenges of oral methotrexate use so that I am able to recognise the needs and potential problems experienced by these patients.

- As an arthritis specialist I need to identify patients who might benefit from the use of oral methotrexate so that their quality of life can be improved, and I need to determine the most appropriate dose of oral methotrexate for the patient so that their condition may be improved.

- As a drug manufacturer I need to supply oral methotrexate in a form so that pharmacies can adjust the quality dispensed to meet individual patient needs, and I need to sell sufficient quantity of oral methotrexate so that the product line is commercially viable.

- As a pharmacist I need to dispense methotrexate in a timely way so that the patient always has the medication they need, and I need to ensure that the patient understands the particular restrictions on the use of oral methotrexate so that they are kept safe.

- As a carer I need to know that the patient understands the importance of taking the correct dose of methotrexate so that they remain safe, and I need to be sure that methotrexate is not confused with other medications so that they remain safe.

- As a phlebotomist I need to collect blood samples from the patient so that methotrexate toxicity tests can be carried out in the hospital, and I need to ensure that any change to the methotrexate dose is communicated to the patient and GP so that they are both informed of the new dose.

- As a pathologist I need good blood samples so that I can test methotrexate levels in the patient’s blood.

- As a software supplier I need to deliver competitive prescribing and dispensing systems so that GPs/pharmacists use my software, and I need to ensure that my products enhance GP/pharmacist practices so that errors are reduced.

- As an information supplier I need to ensure that information is trustworthy and accessible so that GPs/pharmacists use my services, and I need to ensure that my services enhance GP/pharmacist practices so that errors are reduced.

- As a packaging/labelling supplier I need to provide clear identification so that the pharmacist and patient can unambiguously select the correct medication.

- As a practice receptionist I need to ensure that repeat prescription forms are authorised so that patients receive their prescriptions in a timely manner.

- As a practice manager I need to ensure that everyone is aware of our policies and practice relating to methotrexate so that patients receive safe care.

Problem

Prioritise Stakeholder Needs

The needs for redesign of the system are dominated by the needs of the patient, where the priority is for an easy-to-follow medication management process, easy-to-understand information about methotrexate, easy-to-identify medication and easy-to-open packs. Other needs, derived from the stakeholders list, should also be considered in the context of meeting the fundamental patient needs.

Success will be measured by a significant reduction of deaths and serious injury to patients being treated with methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis while maintaining the benefits of disease and symptom control.

Solution

Develop Concepts

In response to the patient needs and risk assessment, a number of potential solutions were identified, each of which would prevent some opportunity for harm and collectively would prevent or reduce all harm based upon the causal and contributory data available at the time:

- Better information for the patient prior to treatment and use of patient-held records to include monitoring schedules and results.

- Clear branding of methotrexate as a weekly medication with clear instructions to take methotrexate on Mondays.

- Improved warnings and flags for GP prescribing and pharmacy dispensing software systems which were not easily over-ridden.

- Reshaped tablets from manufacturers to ensure that 2.5 mg round tablets are easily distinguishable from new 10 mg torpedo shaped tablets.

- Repackaged tablets using novel designs and in reduced quantities so that the patient receives the original manufacturers pack.

Evidence

Review Effectiveness

A new information leaflet for patients, emphasising the weekly dose for methotrexate, was drafted and trialled. This led to the provision of a methotrexate treatment guide incorporating a pre-treatment leaflet, designed to provide patients with guidance on low dose methotrexate, and a blood monitoring and dosage record booklet.

The changes proposed for the shape of the methotrexate tablets were delivered, but this did not address potential confusion with other medications and, in particular, folic acid which is often prescribed along with methotrexate.

Software vendors provided enhancements to their existing GP prescribing software to ensure methotrexate was clearly labelled as High-Alert, Alert or Toxic in the drug list, to generate an additional alert message when selecting methotrexate highlighting the need for weekly doses and to provide dosing options that clearly articulated the number of tablets to be taken.

Novel packaging designs were not pursued at this stage. However, manufacturers began to provide tablets in 16 and 24 packs with improved design (for patients with reduced manual dexterity), labelling and safety information. The use of existing pharmacy labels continued.

Review Safety

A review of the risks associated with the original oral methotrexate system was undertaken prior to determining the design interventions described above. This identified the following high-risk scenarios:

- Failure to identify changed prescription request arising from blood test results.

- GP prescribes methotrexate “as directed”.

- Patient receives wrong dose due to confusion between different strengths of methotrexate tablets.

- Patient receives wrong dose due to confusion between folic acid and methotrexate tablets.

- Patient experiences difficulties reading print on blister pack.

- Incorrect prescription of methotrexate is dispensed to the patient because of poor design of prescribing/dispensing software.

- Pharmacy picking error results in wrong medications being dispensed.

- Pharmacist only writes total dose of methotrexate, not number of tablets.

- Poor hospital drug chart review by hospital pharmacy.

- Poor education of healthcare professionals regarding use of methotrexate.

Many of these issues were addressed by the design changes proposed and other patient safety initiatives. However, a number remained, including the potential for patients to be confused by the two strengths of methotrexate tablets and this led directly to the policy in many regions to prescribe only 2.5 mg tablets. There was also a danger that patients might be confused by the variation in dose that was the direct result of the review of regular blood tests designed to determine the optimal dose for each individual. It was important that changes in dose were communicated clearly to the patient and others in the shared care arrangement to ensure that all patient records were up to date.

Evidence

Review Barriers

Limited data was collected to enable direct comparison with previous error rates and subsequent patient harm resulting from use of oral methotrexate. Communications from the NPSA suggested that early compliance with new guidance remained poor, likely contributing to ongoing errors in the use of

methotrexate, resulting in patient harm.

Eighteen months after the shape of the 10 mg methotrexate tablet was changed the Medical and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) issued a Class 3 Medicines Recall. Original round 10 mg tablets that had remained in circulation alongside the new torpedo shaped 10 mg tablets were recalled as their continued presence had given rise to confusion where patients had been told all round tablets were 2.5 mg.

Despite all the best efforts of the improvement team, methotrexate remains a potentially harmful drug that is ultimately administered by the patient. Deaths and serious harm continued at a lower level and in 2011 a patient, prescribed an increasing dose of methotrexate in order to identify the required level of medication, continued to increase the weekly dose beyond the mandated maximum and died. This was not an error that had been predicted and shows the importance of shared care arrangement team taking full responsibility for all aspects of the prescribing, dispensing and monitoring cycle when working with

patients receiving oral methotrexate.

Case

Present Case for Change

The benefit of reducing the incidence of Methotrexate never events, set against the cost of change, was recognised by the local and national stakeholders brought together by the National Patient Safety Agency.

Plan

Manage Team

People should be involved in the improvement programme if they are involved in the supply, management and control of methotrexate in the UK, such as:

- patients and carers

- community pharmacies

- GPs and hospital doctors

- drug manufacturers

- drug prescription and dispensing software vendors

- information providers and packaging designers.

Review Project Performance

The use of oral methotrexate as a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis relies on a number of systems working with the patient to ensure their safety. Further improvements in the use of this drug will need to follow a systems approach to ensure that key stakeholders work together to identify and implement changes that would minimise future loss of life.

The Esther Model

A multi-organisational collaboration between acute, primary and social care providers was created by Jönköping County Council to develop a model for the improvement of patient-centred care in the community, based on a fictitious patient known as Esther.

Scope

Trigger

Esther lived alone and one morning developed breathing difficulties. After contacting her daughter, who did not know what to do, Esther sought medical advice. She saw a total of 36 different people and had to retell her story at every point, while having problems breathing. A doctor finally admitted her to a hospital ward. This case inspired the head of the medical department of Höglandet Hospital in Nässjö to initiate an extensive series of interviews and workshops to identify redundancies and gaps in the medical and community care systems.

Agree Aim Statement

Elderly patients with complex care needs may receive services from multiple specialists, as well as primary care physicians. In addition, they may visit emergency departments, have frequent hospitalisations and post-hospital rehabilitations, and receive long-term care services at their home or in nursing facilities. The central idea was that care should be guided by the following questions: What does Esther need? What does she want? What is important to her when she is not well? What does she need when she leaves the hospital? Which providers must cooperate to meet Esther’s needs?

Context

Generate Scenarios

The Höglandet (Highland) region (population: 110,000) in Jönköping County, in the south of Sweden, where the county has 34 primary care centres and three acute hospitals, with a total health workforce of 9,500, serving a local population of 350,000 across 11 municipalities.

Understand Patient Diversity

Elderly persons who have complex care needs that involve a variety of providers, along with carers and a number of health and care professionals.

Understand System Context

Care coordination in Sweden is complicated by a legal structure that gives the country’s 21 counties responsibility for funding and providing hospital and physician services while the 290 municipalities are responsible for funding and providing community care. Home health care (nursing services for sick patients) and home care (assistance with activities of daily living) are also provided by different professionals.

Create System Maps

The elements of the system can be considered to be Esther and her family and neighbours, the people who provide all aspects of medical and home care to her, the geographical and transport systems around her home and points of care, the organisations that facilitate her care, and the bodies that fund her care.

Context

Create Stakeholder Needs

Stakeholders are those that have an interest in the successful performance of the system and can be described by their role title, need(s) and purpose:

- As a patient I need care in or close to my home so that I can stay at home, I need to experience care from multiple providers as if it were from the same provider so that they all know my medical history, I need to have care uniformly available throughout the region so that I feel free to travel, and I need to know who to turn to when problems arise so that I feel safe.

- As a carer I need to understand Esther’s needs so that I can help care for her, and I need to know who to call if Esther needs help so that I can be sure of talking to someone who knows her.

- As a neighbour I need to have a contact number for emergencies so that I can quickly summon medical assistance.

- As a primary care physician I need to provide the best care possible for Esther in the community so that her medical needs are met locally as far as is possible, I need access to Esther’s full medical history so that I know what treatment may have been provided by the hospital and what level of social care is being provided.

- As a pharmacist I need access to Esther’s medical history so that I can check that her medications are safe to be taken together.

- As a hospital physician I need access to Esther’s medical history so that I can prescribe the most appropriate treatment, and I need to be sure that appropriate care is available so that I can safely discharge Esther from hospital.

- As a specialist I need access to Esther’s medical history so that I can provide appropriate specialist treatment as required.

- As a nurse I need access to Esther’s medical history so that I can care for her, and I need to know Esther so that I can do what is best for her.

- As a home healthcare worker I need access to Esther’s medical history so that I understand her care needs, and I need to know Esther so that I can do what is best for her.

- As a home care worker I need to have a contact number for emergencies so that I can be sure of talking to someone who knows her, and I need to know Esther so that I can do what is best for her.

- As a hospital manager I need to understand Esther’s care needs so that I can ensure she receives the care she needs and coordinate her discharge from hospital, and I need to ensure she remains in hospital only as long as is medically required so that I can manage my budget wisely.

- As a community care manager I need to understand Esther’s care needs so that I can coordinate her care, and I need to be consulted if she is to be discharged from hospital so that her immediate care needs can be met.

- As a service provider I need to ensure that I meet Esther’s care needs so that I can do what is best for her, and I need to know how well I am meeting her needs so that I can continuously improve the care I am able to provide.

- As a funder I need to be confident that the money I provide for the care of elderly persons is spent wisely so that the benefit of good care is provided for all.

- As an administrator I need to ensure good communication between care providers so that they understand Esther’s medical and care needs and provide coordinated care for her.

Problem

Prioritise Stakeholder Needs

The analysis of interviews with over 60 patients and providers throughout the system identified six key needs for action:

- The development of a flexible organisation with patient value in focus.

- The design of more efficient and improved prescription and medication routines.

- The creation of approaches to documentation and communication of information that can be adapted to the next link of the care chain.

- The provision of efficient IT-support through the whole care chain.

- The provision of a diagnosis system for community care.

- The development of a virtual competence centre for better transfer and improvement of competence through the care chain.

Success will be measured by Esther getting care in or close to home, experiencing care from multiple providers as if it were from the same provider, having care uniformly available throughout the region and knowing who to turn to when problems arise.

Solution

Develop Concepts

Many of the problems experienced by Esther involved more than one organisation. It was important to bring together people from different levels in these organisations to develop and deliver solutions to support the needs identified. These included:

- A steering committee of the community care chiefs from municipalities, hospitals and primary care centres to address challenges across organisations.

- Four Esther cafés in municipalities each year, which were cross-organisational, multi-professional meetings for sharing and learning from the experiences of specific patients who were hospitalised in the past year and have continued on to home care or other services.

- Inter-organisational training workshops on palliative care, nutrition and fall prevention, among other topics.

- An annual strategy day for nurses and other staff, physicians, managers, as well as Esthers themselves to come together to team build and generate priorities and ideas for addressing problems in care.

In 2006 coaches were introduced to the model to promote the Esther Network vision and values and to support ongoing improvement. The aim was to develop internal coaches to facilitate improvement across organisational boundaries, providing: customer focus, modelled by involvement of senior citizens in the training programme; a shared set of values; networking skills with a solution focused approach; and systems thinking.

Evidence

Review Effectiveness

The Esther model calls for continuous and coordinated improvement with a focus on providing what is best for Esther. The evidence points to a cultural shift in the way leaders and workers in the Jönköping County health and care systems now provide for Esther, facilitated by the solutions introduced in response to her needs — “the focus is on her now.” It is also evident that the changes have not only been sustained and further developed, but also have provided the inspiration for change in other health and care systems around the world.

Review Safety

Proactive risk assessment was not employed within this programme. However, the impact of the changes introduced were continuously monitored.

Review Barriers

This innovation programme was not designed as a research project and involved many organisational and process changes that were introduced in different components of the model at different times. Therefore, it is important to be cautious in assessing the impact of the Esther model.11 Positive changes are noted, but it is difficult to attribute them to the model in the absence of comparative information. With this in mind, programme leaders cite the following outcomes:

- Admissions to the medical department of Höglandet Hospital declined from 9,300 in 1998 to 6,500 in 2013.

- Hospital readmissions within 30 days for patients age 65 and older dropped from 17.4% in 2012 to 15.9% in 2014.

- Hospital lengths of stay decreased between 2009 and 2014 for surgery (from 3.6 to 3.0 days) and rehabilitation (from 19.2 to 9.2 days).

- Surveys conducted in Jönköping in 2008 and 2011 showed that Esthers felt safe and were appreciative of the personal contacts.

Case

Present Case for Change

The benefit to Esther and the value, set against the costs to integrate care, was recognised by all of the acute, primary and social care providers collaborators brought together by Jönköping County Council.

Plan

Manage Team

Patients and carers, and people involved in the supply, management and control of care for elderly people, such as physicians, nurses, social workers, other providers representing the Höglandet Hospital and physician practices in each of the six municipalities.

Review Project Performance

“Taking a system approach to meeting the needs of the frail elderly is unusual, difficult, and necessary.” The Esther model depends on “the power of patients’ stories”, which were elicited and collected as part of the model to show how patients’ lives are affected by their health challenges and their experiences in getting care. The model creates mechanisms, including an annual retreat and development of action plans for each forthcoming year, to help members of different professions to continue to think together to solve problems and help to motivate the coaches. “The secret of Esther is the change in state of mind — stop thinking what is best for my organisation, but instead think what is best for Esther.”

Feedback

We would welcome your feedback on this page:

Privacy policy. If your feedback comments warrant follow-up communication, we will send you an email using the details you have provided. Feedback comments are anonymized and then stored on our file server

Read more about how we use your personal data. Any e-mails that are sent or received are stored on our mail server for up to 24 months.